Imperial dreamings

AMBER HOUSE - at the centre!™ a Bed and Breakfast Guest House (B&B) in Nelson city centre - handy for Tahunanui Beach, Restaurants, Founders Park

and the 3 National Parks of Abel Tasman, Kahurangi and Nelson Lakes in the `Top of the South' Island of New Zealand (NZ).

This is the text inscribed on the brass bell that hangs at the door of Amber House:

"

Cabragh House School

rings out loyal greetings

to His Majesty today

when the Colony of New Zealand

becomes a Dominion.

May God grant that Ireland is next!

God save the King

26th September 1907 "

It is little known that Māori men had universal suffrage in 1867 (for the Maori seats) - 12 years before Pākehā (European) men; or

that a Māori was elected in a general electorate seat (by Pākehā voters) as early as 1893 - the same year that women could vote in New Zealand.

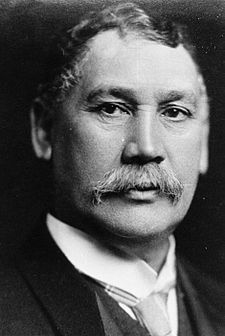

That same general electorate MP, James Carroll or

Timi Kara, went on to become, very briefly in 1909, New Zealand's acting Prime Minister. He was of Ngāti Kahungunu and Irish ancestry.

It is little known that Māori men had universal suffrage in 1867 (for the Maori seats) - 12 years before Pākehā (European) men; or

that a Māori was elected in a general electorate seat (by Pākehā voters) as early as 1893 - the same year that women could vote in New Zealand.

That same general electorate MP, James Carroll or

Timi Kara, went on to become, very briefly in 1909, New Zealand's acting Prime Minister. He was of Ngāti Kahungunu and Irish ancestry.

In 1887, while an MP for a Māori constituency, he argued in parliament that all unnecessary distinctions in law and administration on the basis of race should be removed; that the same laws of property and rights of citizenship should apply to all, and that a select committee should be appointed to consider means 'by which equalisation may be expedited'. Not surprisingly, these sentiments were hurled back in his face by the opposition throughout his parliamentary career whenever Carroll proposed special provisions for Maori.

However, the passages below hint at the historical context in which Mr Hornsby (presumably?) commissioned this Cabragh House bell more than 100 years ago:-

The Right Honourable Richard John Seddon, P.C., LL.D., Premier of the Colony of New Zealand, asserted the importance of Great Britain establishing and maintaining supremacy in the Pacific. He wrote to a friend in England a few months before his sudden death:-

“The Pacific Islands question is of paramount importance. Under the altered conditions now existing, which in the future will be greatly changed, to the advantage of other nations, by the construction of the Nicaragua and Panama Canal, numbers of industries will be greatly affected. In fact, it is difficult to grasp the momentous issues involved. Unless British statesmen grasp the situation and provide therefor, they will find in years to come the weak spot. They will discover that the most deadly blow will be struck at our Empire in the Pacific itself.

“The Japanese have stopped the Russians in the East, and what is going to happen in the West, who can tell? It is well ever to be prepared. With industries crippled and food supplies stopped, the people in the heart of our great Empire will be in a bad way. It is not too late for action. Prevention is better than cure, and we must be up and doing. If our kindred at Home do their part, then the self-governing colonies will not fail when the occasion arises. Meantime, wherever possible, the British flag should float over the islands of the Pacific.”

On several occasions, he referred to his policy of annexing islands to New Zealand, and he remarked: “I never stood such jeering as when I was fighting this question.”

He spoke in angry tones of the apathy of British statesmen in this respect:-

“They foolishly lost Samoa. The steamer was there tearing at her hawsers, and everything was in readiness to take possession. The king and islanders were prepared to be annexed - in fact anxious to come in with New Zealand - but Downing Street intervened, and Samoa was lost and given to America. Great credit is due to Sir Robert Stout and Sir Julius Vogal for the effort to save Samoa. The imperial statesmen did not grasp the full significance of the loss of this and other islands. New Zealand was injured, as Samoa was close to it and lay on the track of the West. Through their muddling and through their mistakes irreparable injury was done to New Zealand by the British statesmen of that day.

“As to the Sandwich Islands, the Republican Government was prepared to support a protectorate under America and Britain. I interviewed John Sherman, Secretary for Foreign Affairs, on the subject, but that gentleman told me there was no danger. To interfere with these islands, said Mr. Sherman, would be contrary to the Monroe Doctrine, and he did not himself approve of a protectorate. America, he said, would be true to her Monroe Doctrine. I then saw President M'Kinley, who put quite a different complexion on the position. He said, ‘You know, Mr. Seddon, American interests are so great — there is so much American capital there: there is the cane interest of San Francisco, then there is the beetroot sugar question — that we find great difficulty in our country in that respect, and it is important to us. And,’ said he, ‘I will urge all I can that those islands shall be annexed to America.’

“I subsequently saw the representative of Great Britain on arrival in England, and made representations strongly urging that, in the interests of the Empire and New Zealand, British statesmen should do their duty and save these islands. At that time a third of the boats trading between San Francisco and New Zealand belonged to New Zealand. They were doing a large business with Hawaii, and I knew that if the American coastwise laws were to be applied New Zealand steamers would be shut out. Two of the Ministers of the islands were New Zealanders, and the majority of the Sandwich Islanders wanted the islands to be British, and my idea was to have a protectorate as a step in that direction. Further representations were made in London, but they were pooh-poohed. America, they said, would never annex; but within three years those valuable islands formed part of the American Republic, and British and New Zealand trade was shut out.

“Then with regard to Noumea, Sir George Grey urged, as far back as 1853, that it should form part of New Zealand — and the chiefs wanted to be annexed to New Zealand — they wanted it to be British. Sir George begged Downing Street to make the annexation, but, apparently, from sheer indifference, no action was taken. Shortly after that the Marist Brothers arranged with some agents who were there, the French hoisted their flag, and Noumea and New Caledonia became annexed to France. These losses were incalculable, and it was a pity that such statesmen should ever have been entrusted with the destinies of Great Britain.

“The Philippines are also American. Undoubtedly America is pursuing an inter-island policy, and has entirely departed from the Monroe Doctrine. It was only the other day that President Roosevelt said that the Stars and Stripes, should dominate the Pacific. I say the flag that should dominate the Pacific is the Union Jack.

“In New Zealand we are face to face with the New Hebrides difficulty. At one time the New Hebrides actually belonged to New Zealand, having been included in the latitudinal and longitudinal bearings, but subsequently this was altered and the islands were left out. I wish that they had been allowed to remain. They are valuable islands and are close to New Zealand, only about four days away.

“A long time ago a despatch was sent from this country to the British Government, in which it was plainly and distinctly laid down what was believed to be a proper course for the British Government to follow. Some other arrangement should have been made with France, in the way of compensations, or concessions elsewhere, in consideration of her ceding her claims in the New Hebrides to Britain. As things are, it would be better if they divided the New Hebrides, Britain taking one part and France the other. The protectorate between the two nations is dangerous, as it may lead to friction between the two Powers, and ultimately end in Britain ceding everything to France. In these matters the Opposition should join with the Government. In all such cases party matters should be sunk, and we should stand together for the good of our colony and the advancement and solidarity of the greatest Empire the world has ever known.”

Seddon's Funeral

Soon after day-break on the morning of the day of the funeral, June 21st, 1906, Māori mourners began to assemble at the Parliamentary Buildings. There were several hundreds of them, and they represented nearly all the New Zealand tribes. A few tribes, who were not present, sent messages of sorrow.

At 7.45 a.m., the coffin was carried into the lobby of the House of Representatives by a company of the New Zealand Permanent Artillery. It was followed by the Hon. W. Hall-Jones (the new Premier) and other Ministers, and Mr. Seddon's sons and other male relatives. Some of the chiefs had placed on the floor, beneath the picture of Queen Victoria, some beautiful flax cloaks and mats. These were the “hopaki,” or wrappings for the coffin. Treasured ancestral weapons, taiahas and mérés, were placed on the floor beside the coffin. They were gifts in honour of the dead.

Behind the chief mourners and the Ministers there followed several old friends of the late Premier. They remained there for a few minutes, and then quietly left the lobby, which was given up to the Māoris.

A woman's high-keyed voice, raised in the opening cries of a tangi-wail, was heard, and the Māoris, in a compact body, with the women in front, marched in. About fifty women formed this advance-guard of the “bringing of the tears,” as the Māoris call it. They trod slowly, turning this way and that way, but always keeping their heads bowed, until the front rank was close to the coffin. All the women of the tribes were of high birth and station. Most of them had blue tattoo marks on chins and lips, the cherished “tohu.” All were dressed in black. From their ears, hung by black ribbons, and around their necks, they wore greenstone ornaments and glistening white sharks' teeth, as in olden days. On their heads and shoulders there were green leaves and chaplets, the ancient insignia of mourning. They carried green branches in their hands, and kept time with these to the shrill dirge: “Haehaea! Ripiripia!” “Score the flesh; scarify your bodies as with knives!” This was the burden of their opening song, and they kept time to it, drawing their hands up and down and across their breasts and shoulders, in imitation of the ancient funeral custom of lacerating the flesh with flakes of obsidian or mussel-shells.

In front of these women there came a chieftainess from the Wanganui district, Wiki Taitoko. She is a daughter of Major Kemp, and a woman of commanding presence. With Utauta, a lady of rank from the Ngatiapa tribe, she gave the time to the main body of mourners in the “maimai,” the chant and dance of grief.

The men strangely and strikingly represented the old and the new. There were men who had fought for and against the Europeans in the Māori war. A college-bred Māori member of Parliament stood side by side with old Poma Haunui, whose deeply tattooed face singled him out for notice. He is one of the few survivors of a gallant band of friendly Māoris who defeated the rebellious and fanatical Hauhaus on Moutoa Island, in the Wanganui River, in 1864, and saved the Wanganui settlement. Tuta Nihoniho is chief of the Ngatiporou tribe on the East Coast of the North Island. He and his tribesmen were always friendly. He holds the New Zealand war medal for his services with Major Ropata Wahawaha, in the Urewera campaigns of 1869–71. Near to him there stood Tutange Waionui, who was a Hauhau in his younger days, and was one of the most active scouts of the famous Hauhau leader, Titokowaru, in the Taranaki war. The most conspicuous figure of them all was that of the Hon. James Carroll, the Native Minister, one of Mr. Seddon's colleagues.

The first wild burst of the “maimai” song subsided. The swaying women seated themselves on the floor and left a narrow lane, through which one or two chiefs advanced to place fine mats beside the other Māori treasures at the side of the coffin. The hum of weeping rose, led by the old tattooed ladies of Ngatikahungunu and other tribes. The Wanganui men, led by their chief Takarangi Mete Kingi, who quivered a polished méré in the air, chanted in chorus one of their laments.

Mr. Carroll addressed the Māoris. “Haere mai e te iwi takoto nei,” he said; greeting to all the tribes from both islands. Their shelter had gone, their provider had been taken away.

The noble totara tree had fallen, cut off by the axe of Death. He had gone to the Great Night. Nothing could stay the hand of Death, but loving messages of sympathy could, perhaps, do something to assuage the keen sorrow of the bereaved ones. In that spirit it was desired to present the widow and children of the late Mr. Seddon with the Māoris' “mihi,” their loving message of sorrow and condolence.

Turning to the sons of the late Premier, Captain Seddon, and Messrs. T. Y. Seddon and Stuart Seddon, Mr. Carroll said that the whole of the Māori people felt most poignantly the death of their parent, and he trusted that if anything could in any way temper the sorrow of the afflicted family, it would be that little tribute of affection and grief from the native race.

He read from an engrossed scroll an address to Mrs. Seddon in Māori and English. It had been signed by more than 100 Māoris, men and women. The English, which was drafted by Messrs. Heke and Ngata, is as follows:-

To Mrs. Seddon. In Memory Of Richard John Seddon, Premier of New Zealand, From The Māori Tribes of Aotearoa (North Island) and Te Waipounamu (South Island).

“Remain, O Mother, with thy children and thy children's children! Tarry ye a while in the house of mourning, in the chamber of Death. Clasp but the cold form of him who was to thee husband beloved. He is now from thee parted, gone into the Dark Night, into that long, long sleep. God be with thee in thine hour of trial. Here he lies in the calm majesty of death.

“Rest, O Father! The tribes have assembled to mourn their loss. Aue! The canoe is cast from its moorings, its energy and guide no more. The redhued bird, the Kaka-kura,* the ornament of Aotearoa, the proud boast of the Waipounamu, the mighty heart of the land, the moving spirit of the people—fare thee well, a long farewell! Pass on, O noble one, across the long sands of Haumu, beyond the barrier of Paerau—going before to join the illustrious dead. Woe unto us that are left desolate in the Valley of Sorrow. In life thou wert great. Across the Great Ocean of Kiwa,† beset by the turbulent waves of faction, mid the perverse winds of opinion, thou didst essay forth that thy peoples should reap of benefits, that these islands and thy mother race should see and do their duty in the broader spheres of Empire and humanity. Fate, relentless, seized thee in the mid-ocean of effort, and compelled thee into the still waters of death, of rest.

* The red parrot. † The Pacific Ocean.

“Sleep thou, O Father; resting on great deeds done, sure that to generations unborn they will be as beacons along the highways of history. Though thou art gone, may thy spirit, which so long moved the heart of things, inspire us to greater, nobler ends.

“Stay not your lamentations, O ye peoples, for ye have indeed lost a father. Verily our pa of refuge is razed to the ground. The breastwork of defence for great and small is taken. Torn up by the roots is the overshadowing rata tree. As the fall of the towering totara tree in the Deep Forest of Tane* (Te Wao-nui-a-Tane), so is the death of a mighty man. Earth quakes to the rending crash. Our shelter gone—who will temper the wind? What of thy Māori people hereafter unless thou canst from thy distant bourne help and inspire the age to kindlier impulse and action!

* Tane, the God of the Forest.

“So bide ye in your grief, bereaved ones! Though small our tribute, our hearts have spoken. Our feet have trod the sacred precincts of the court-yard of Death (te marae o aitua). Our hearts will be his grave. Love will keep his memory green through the long weary years. Hei konei ra! Farewell!”

Mr. Carroll concluded his oration by chanting a fragment of a beautiful old funeral dirge of his race:-

No te ao te hua ra tanga

Riro ki te po.

Waiho noa hei tumanako

Ma te ngakau.

Kei tawhiti to hou tinana,

Kei te reo o tuku;

Tenei au e noho ana

I te pouritanga,

Mapu kau noa atu i konei.

Au koha hau raro——i !

By day what thoughts of thee arise!

But thou'rt vanished in the Night of Death!

Naught is left my heart to cherish

But fond longings—fond and vain.

Far, far away thy form has taken flight;

Far, far thou'rt severed from my side,

And spirit voices breathe thy name.

Here in this lonely world

I sit with drooping head

And nurse my grief in depths of black despair.

Yet on the gentle northern breeze

Thy tender message, loved one, ever sighs to me.

Then tribe after tribe rose to pay tribute to the dead. Chief after chief stood up to deliver his “poroporoaki,” his salute to the spirit of Te Hetana.* Up rose Hori Te Huki, a grey old chief of Ngatikahungunu. “Haere atu, e koro! Farewell, O Old Man!” he cried. “Go thou to that last dwelling-place to salute thy honoured ancestors, to greet the spirits of the mighty dead.”

* Mr. Seddon.

Then Te Huki broke out into a plaintive lament, in which all his people quickly joined in a resounding chant. It was an ancient lament by a widow for her departed husband:-

Restless I lie

Within my lonely house,

For the loved one of my life

Has passed away.

The singers, their voices rising and falling in wild cadences, went on to compare the dead chieftain to an uprooted tree: “My shelter from the blustering wind, alas, 'tis now laid low.”

Then the poet developed another beautiful piece of imagery:-

Behold yon glistening star so bright -

Perhaps 'tis my beloved friend,

Returned to me again.

O sire, return!

And tread with me again

Thy old loved paths.

Changing the metaphor again, the mourners chanted all together:-

O thou that art gone,

Thou wert as a great canoe

Decked with the snowy down

Of lordly albatross.

In another dirge, introducing many mythological allusions, the poet said:— “Thou'rt borne away in the canoe Rewarewa; snatched from us by the gods Raukatauri and Ruatangata. Dip deep the paddles, all together, to bear thee far away.”

Eruera te Kahu and Ratana Ngahina, chiefs of the Ngatiapa tribe, led their people in the singing of this finely-phrased mourning chant, an adaptation of an apakura:-

Haere ra, Hetana, i te ara haukore,

Taku ate hoki ra, taku pa kairiri

Ki te ao o te tonga;

Taku manu-korero ki te nohanga pahii,

Taku manu hakahaka ki runga ki nga iwi.

Houhia mai ra te matua

Ri te kahu Tahu-whenua;

Houhia mai ra te matua

Ki te kahu Taharangi.

Marewa e te iwi

Nana i whitiki taku motoi-kahurangi,

Ka mau ki te taringa;

Taku koko-tangiwai

Ka mau ki te kaki:

Taku pou-mataaho e tu i te whare.

Kia tu mai koe i te ponaihu o te waka,

Kia whakaronga koe te wawara tangi wai hoe,

I roto Poneke,

I te Runanga-nui,

Waiho i muri ne i to pukaikura—i!

Pass on, Hetana, along the quiet ways,

The beloved one of my heart, my shelter and defence

Against the bleak south wind.

My speaking-bird that charmed the assembled tribes,

That swayed the people's councils.

Clothe him, the Father, with the stately garments,

The very fine mats Tahu-whenua and Taharangi,

Place in his ear the precious jewel-stone,

The greenstone kahurangi,

Hang on his breast the koko-tangiwai,

Of glistening lucid jade,

Oh, thou wert a prop within the house;

At the prow of the canoe thou wert,

Ears bent to the plashing sound

Of many paddles

In the waters of Poneke,*

In the contentions of the People's Council.

Our prized kaka-bird has gone,

The plumes alone remain.

* Port Nicholson, the former name of Wellington Harbour.

Then came the chiefs of the Greenstone Land. A big half-caste chief, Timoti Whiua, who is better known as George Robinson, of Little River, Canterbury, chanted his dirge with a force and intensity that thrilled his hearers. In a short address to the dead Premier, he referred to him as the sweet-singing bird of the dawning day, the bright star of the morning, the great one of the earth. He then sang:

Keen blows the nor'-west wind,

Wind from the Mountain-land,

Bringing sad thoughts of thee.

Where, O Hetana, art thou gone?

Perhaps in council-hall thou'rt laid,

To await thy people's coming.

Yes, there lies thy mortal shell,

Resting at last

From its many, from its innumerable travels,

From its ceaseless going to and fro.

Yes, thou return'd'st to thy people

Round yonder mountain-cape,

Back to thy dwelling-place—

Rest from thy travels!

O well-beloved one,

Sharp pangs dart through my soul,

O lordly totara-tree,

The pride of Tane's woods,

Thou'rt lowly laid,

As was the canoe of Rata,

The son of Tane launched

For vengeance on the slayer Matuku,

Who soon himself was slain.

'Twas thou alone that Death didst pluck

From the midst of living men,

And now thou stand'st alone

Like the bright star of morning;

For us naught but sad memories;

Sleep soundly, Friend!

Wi Pere, who represented the Eastern Māori district in Parliament for many years, was the next speaker. “Farewell,”' he cried, “Farewell, O friend of mine! Depart to the Great Night, to Po, that opens wide for you.” When he began his tribal funeral chant he was joined by his people of Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki, Te Rongowhakaata, and Ngatiporou in the stentorian song:-

Farewell, O Friend!

Depart to thine ancestral company.

Thou'rt plucked from us

As the flax-shoot is plucked from the bush

And held aloft among the mourners.*

Thou that wert our boast, our pride,

Whose name has soared on high,

Thy people now are lone and desolate.

Indeed thou'rt gone, O Friend!

Thou'rt vanished like our ocean-fleet of old—

The famed canoes, Atamira, Hotutaihirangi,

Taiopuapua, Te Roro-tua-maheni,

The Araiteuru! and Nuku-tai-memeha,

The canoe that drew up from the sea

This solid land.

* The reference to the plucking of the flax-shoot is in connection with the methods of divination practised in ancient time by the tohungas, or

priests, before a war-party set out on the enemy's trail. The reader of the omen plucked the “rito” or central shoot of a flax-plant. If the end broke off

evenly and straight, it was a good sign, presaging an easy victory. If it was jagged and gapped, or torn, that was a “tohu kino,” or evil omen, a warning

that a leading chief of the war party would be slain. The ancient canoes named were some of those which brought the ancestors of the East Coast tribes to New

Zealand from the islands of Polynesia. The Araiteuru is the sailing canoe which was wrecked on the beach near Moeraki six centuries ago. Nuku-tai-memeha is

one of the mythological names of the canoe from which, in the days of remote antiquity, the great god Maui fished up the North Island of New Zealand.

Wi Pere began again, and all his people chanted with him:-

Affliction's deepest gloom

Enwraps this house,

For in it Seddon lies

Whose death eats out our hearts.

'Twas he to whom we closest clung

In days gone by.

O whispering north-west breeze,

Blow fair for me,

Waft me to Poneke,

And take me to the friend I loved

In days gone by.

O peoples all and tribes,

Raise the loud cry of grief,

For the Ship of Fate has passed

Port Jackson's distant cape,

And on the all-destroying sea

Our great one died.

The final scene in the “tangi-hanga” was a dramatic climax. Both Māoris and Europeans had been wrought up to a deep feeling by the songs, the high-pitched cries of farewells, and Hone Heke, M.H.R., the last of the speakers, gave the old farewells, and then Takarangi Mete Kingi rose to his feet, and, circling his méré round his head, cried the opening words of the lament:-

Whakarongo e te rau

Tenei te tupuna o te mate.

The Māoris sprang to their feet and broke into a grand chorus, an old chant to Death. They stamped and threw their arms from side to side. The women waved their green branches, and as the sonorous poem was chanted with full voice, they seemed to be defiantly challenging Death. No translation can convey the pathos and poetic force of the lament, but the words may be given. They are as follow:—

Hearken O ye people!

This is the parent of Death,

Our common ancestor,

Who must embrace us all.

'Twas conceived in the Reinga,*

'Twas engendered in the Dark, Sad Night.

'Tis but a breath from heaven,

And we pass away for ever.

We fall, and prone we lie,

And ever soundly sleep.

We slumber with our knees drawn up,

We slumber stricken in a heap.

I liken me to yon bright starry sign,

To Maahu-tonga†

That round and round revolves.

(We circle our short lives and then pass on),

I am but as a wandering sprite—

Behold the hawk that soars so far above

In summer skies—

And listen to the sullen matuku,

The bittern†† that bellows in the swamp

(E hu ana i to repo—i—e!)

* Te Reinga, the Māoris' name for Spirits' Bay, where, it was thought, spirits of the dead departed from this world for the other world.

† The Southern Cross.

†† The matuku, or bittern, apparently, is taken as the symbol of death.

With eyes rolling, feathers dancing, black tresses tossing, and weapons brandished in the air, the Māoris ended their great song with a long drawn “E—e!” Takarangi, still quivering his méré in an excited hand, cried his loud farewell, higher and higher until he almost screamed it:-

“Farewell! Depart! Depart!

And greet your many ancestors.”

Then he snatched up a soft flax mat on which he had been kneeling, and, advancing, placed it at the foot of the bier. There arose again the wild heart-breaking cry, “Haere atu, Haere atu E Koro!” “Go, O, Old Man, to That Place, That Place!”

Subsiding into respectful silence, after their excited outburst, the Māoris formed up in line, and with bowed heads and tear-stained faces, filed past the coffin in order to shake hands with the Premier's sons and take their last look at their friend.

The body lay in state for three hours, and thousands of the dead Premier's “subjects,” as many of them loved to call themselves, passed in front of it. There was a service in the pro-cathedral, and the procession followed the remains to Observatory Hill, where the worker found a resting-place. On the day of the funeral, the whole colony was in mourning. The occasion was absolutely unique. One impulse ran through the whole community; one thought prevailed; and one sentiment was in all breasts. The man who had stood at the head of the administration for thirteen years, who had toiled with the people and for them, and who had been called suddenly away, was in every mind. They saw him again, as they had known him best, with his kingly presence and his majestic bearing, when he loved to come amongst them, listening to their troubles, inquiring into their grievances, righting their wrongs, and granting their petitions with the air and grace of a mighty monarch. He had had many enemies, as well as many friends, but all joined in reciting the good he had done, and extolling his splendid qualities.

The sorrow caused by his death was felt in all parts of the Empire. When the news was announced to the world, messages of condolence were sent to New Zealand.

The Secretary of State for the Colonies sent the following messages to the Hon. W. Hall-Jones:-

“I am commanded by His Majesty to convey to you the expression of the deep regret with which he has received the intelligence of the death of the Prime Minister of New Zealand. His Majesty is assured that the loyal and distinguished services which Mr. Seddon has rendered during his long tenure of office will secure for his name a permanent place among the statesmen who have most zealously aided in fostering the sentiment of kinship on which the unity of the Empire depends.”

“His Majesty's Government have received with the greatest regret the news of the death of the Prime Minister of New Zealand. Please convey to Mrs. Seddon expressions of my deepest sympathy, and to the people of New Zealand our sense of the loss which they and we have all sustained by the removal of a statesman so distinguished in the history of the colony and the Empire.”

The Queen's message to Mrs. Seddon was as follows:-

“Accept my deepest sympathy in your overwhelming sorrow, which the whole of England shares.”

The Prince of Wales sent the following message to Mrs. Seddon:-

“The Princess of Wales and I are deeply grieved at your irreparable loss. We shall never forget your dear husband's kindness to us in New Zealand.”

Sir Joseph Ward, who was in London, sent the following message to the Mayor of Hokitika:-

“The hearts of the people of New Zealand are saddened by the removal of the representative of Westland from the control of the colony's public affairs. The Empire, whose interests were ever uppermost in his mind, will feel the loss of Mr. Seddon's powerful advocacy for its welfare. Among those who will miss his great public figure most will be his steadfast friends of Westland. The miners have lost a true friend and champion, and all classes will join me in tendering his wife and family their deepest possible sympathy.”

The High Commissioner in London received the following letter from Mr J. Chamberlain:-

“Dear Mr. Reeves,—I have seen, with the deepest regret, the news in the paper this morning of the sudden death of my friend the late Prime Minister of New Zealand. I have ventured to cable a short message to Mrs. Seddon, but desire also, through you, as the official representative of New Zealand in this country, to express my keen sense of the loss the colony has sustained by the death of its able and patriotic leader. On the various occasions on which I had the pleasure of meeting him, I formed the highest opinion of his ability, courage, and devotion to the interests of New Zealand, while I had full opportunity of recognising his far-seeing appreciation of the privileges and responsibilities of the Empire in which he so earnestly desired that New Zealand should take her appropriate place. At the time of the South African war, he was the first to appeal to his fellow-colonists to give a practical proof of their sympathy with the Mother Country in her time of trial, and he induced New Zealand to offer a larger material assistance both in men and money than any other British colony in proportion to their wealth and population. The spirit which moved him then is to be found in almost his latest spoken words delivered at Sydney just before he sailed for what has proved to be his last voyage. During his long conduct of affairs the colony has made splendid progress in all that constitutes the true greatness of a people, and his friends looked forward to a continuance of his valuable life as a guarantee for the advancement of the interests to which he had devoted himself with so much energy and power. The Empire has lost one of its noblest citizens, and the colony a great administrator, while in our personal capacity Mrs. Chamberlain and I sincerely deplore the death of one whom we were proud to number amongst our friends.

“I beg you to accept the assurance of our heartfelt sympathy with his family and with the colony which he served so well.”

About forty members of the Imperial Parliament, representing all parties, assembled in one of the committee rooms of the House of Commons and passed a motion of condolence. Sir Joseph Ward, who was present by invitation, acknowledged the appreciation. At a meeting of members of the Independent Labour Party in the House of Commons, a motion was passed expressing condolence with Mr. Seddon's family and admiration for the social work of the Government he had led.

In the Federal Parliament of Australia the following motion, moved by Mr. Deakin, the Premier, was passed:-

“That this House places on record its profound regret at the untimely decease of Mr. Seddon, and expresses its deep sympathy with his family and the people of New Zealand.”

When the session of the New Zealand Parliament opened on June 28th, Mr. Hall-Jones, as Premier, moved in the House of Representatives:-

“That this House desires to place on record its high sense of the devoted and distinguished services rendered to New Zealand and to the Empire by the late Prime Minister, the Right Hon. Richard John Seddon, P.C., and of the loss the colony has sustained by his death; and respectfully tenders to Mrs. Seddon and her family an assurance of its sincere sympathy with them in their bereavement.”

The motion was seconded by Mr. W. F. Massey, leader of the Opposition, and after he had spoken the members present rose to their feet while the Speaker put the motion, and remained standing until he had declared it carried. A similar motion was carried in the Legislative Council.

The newspaper press in all parts of the Empire united in praising him. One of the most interesting eulogies published in the press was written by Sir William Russell to the editor of the Lyttelton Times, in which Mr. Seddon's old opponent said,-“At the moment of a great tragedy it is difficult to judge accurately of the character of the hero, difficult also to define a true perspective of the work on which he had been engaged while that work is still new, and much of it incomplete. It is about a quarter of a century since first I remember him sitting somewhere about the centre of the House of Representatives— aggressive, arrogant and resolute, caring little for the forms of the House, less for the opinions of those opposed to him—essentially a man, a man of the rough and ready type, a typical representative of a mining community, vigorous, alert, intelligent, but unrestrained, in marked contrast to his leader, Sir George Grey, calm, critical, controlled. And yet one reacted on the other. The old statesman acquired practical experience of the views of a new democracy; the young politician learned the art and craft of government.

“In our own Parliament he has been a New Zealand Bismarck—of indomitable will and endless fertility of resource—and he unquestionably deserves the epithet ‘Great!’ It may be objected that many of the measures he placed on the Statute Book were not of his own origination, but he had, at least, the wisdom to know what the people wanted, and the personal influence which persuaded an often unwilling Parliament, and the tactical ability to realise what he might insist upon.

“Many have asked, ‘Had Mr. Seddon enjoyed the benefit of a university education would he have been a greater man?’ I doubt it. Education polishes the exterior, but God alone creates the material out of which a man is fashioned. Many are dwarfed by fears of precedent, and the personality and inherent force of any but the strongest men may be contorted by the formalism of too much training. Possibly Mr. Seddon would have been less great had early discipline taught him to consider more carefully the conventionalities of the world. His genius had greater scope owing to an untrammelled brain.”

Many poems have been composed in his honour. The following three, all by New Zealanders, are amongst the best:-

Rest, Premier, rest:

The end of strife has come,

Thy strenuous life has reached its peaceful close:

Throughout the land is hushed its busy hum,

With slackened pulse the life within it flows:

What grief was this, that held a people dumb?

From each has passed a dear-loved, faithful friend,

And wet, blurred eyes are dim to see the end

To this our woe of woes;

Rest, Premier, rest.

Sleep, Leader, sleep.

Whose ardour never slept;

Thy teeming brain has borne abundant fruit;

Before thy fellows thou hast proudly stept,

Regardless of flung scorn and rancour's bruit.

Whom thou hast led thou leavest, not unwept;

hough blossoms fall, the fruit will yet mature;

Thy works with thy young nation will endure,

Deep runs their well-struck root;

Sleep, Leader, sleep.

Rest, Toiler, rest;

In regions of dim dawn,

Through social wildernesses thou hast led,

Nor climbed alone, but all thy people drawn

To sunny heights; but now thou liest dead,

Like that old seer on Pisgah's upland lawn:

Though we behold the land of promise near,

Our leader leaves us with our hope, our fear—

God called him; bow the head.

Rest, Toiler, rest.

Peace, Statesman, peace.

Do we with blinded eyes,

And hearts too fond, exalt thee o'er thy peers?

A voice, no echo of our own, replies

(And each sad heart rejoices as it hears):

“Of him who now forever silent lies

We know the worth; a life yet promise-filled

Has passed away; a mighty heart is stilled.”

With our tears flow their tears;

Peace, Statesman, peace.

Sleep, Father, sleep.

To prove the love we bear,

May we accomplish that by thee begun;

What thou triumphant daredst, may we dare;

What thou wouldst do, may that by us be done.

Father ! thyself thou wouldst not respite, spare —

Shall we then sit and wait?

Nay, rather spend Our lives as thine was spent, that so our end,

Like thine, may worth declare.

Sleep, Father sleep.

Rest, Premier, rest:

Premier in very deed

As we have known, as sister States have known.

Thy words prophetic hitherward did speed—

“I leave for God's own country,” and alone

We wait, and hope, yes hope, with hearts that bleed.

Thy soul was borne from life that knows not ease,

Thy body tossed upon the billowy seas

Mid brackishness and moan,

Rest, Premier, rest.

Sleep, loved one, sleep:

Our cheeks with waiting burned,

Through calm, cold nights, and frore midwinter days:

No heart but day and night to theeward turned,

No eye but seaward did expectant gaze;

No friend but for his leal true comrade yearned.

Thy faults though seen, what could they but endear

Thee to us all? — and now thou canst not hear

Our sorrow or our praise;

Sleep, loved one, sleep.

Peace, War-king, peace:

Triumphant in the fight,

In midst of victory thou hast found thine end;

Old errors vanquished, lo ! the cause of right

Has found thee life-long champion, life-long friend.

The nation thou hast welded moves in might,

And as thyself was known o'er sea and land,

Mav it in van of nations purely stand;

And now — God us defend.

Peace, War-king, peace.

Out of the West, sound sleeping,

Heedless now of the change of dawn and sunset,

Dreaming deep of the olden clamour and onset,

Wrapt in peace and swayed in the passionate swell

Of hurrying waves high leaping

To foam farewell.

Home to the hills that mourn him!

With silence set on the lips that laughed and lightened,

Darkness set in the clear grey eyes that brightened

When once he swept the strings of the songful days.

High, high, pale Death has borne him

By far, dim ways.

Vain now the trumpets' blaring,

The bright, blithe cheers and shouts of the hearts that love him

Wishful only of peace and the grass above him,

Out of the dark strange sea he is seeking rest.

Ended his strong wayfaring —

Closed his long quest.**Johannes C. Andersen.

** From the “Lyttelton Times”

Our days go heavily onward,

The light that lit us of old is no more shining;

The dark has hidden our path beyond divining;

The soul that saw the East where the morning gleams

Has swept in a long flight sunward

With all its dreams.

Far past our utmost knowing!

Tears, or desirous hearts, or the death flag streaming

Vex him not in the deeps of his secret dreaming;

Passion he knows no more, nor the face of woe,

Where poppies of peace are glowing,

And sweet winds blow.* M. C. Keane.

* From the “New Zealand Times” (Wellington) and “Bulletin” (Sydney).

I.

What does he see, what does he hear,

Through the Future's vistas streaming-

He whom we saw on his tragic bier,

And bore to his rest on the hillside here,

On the darkest, saddest day of the year?

Does he look on the sordid scheming

Of puny pigmies for power and place?

Does Grief's black wing throw even a trace

Of shadow over his placid face?

What does he see in his dreaming?

II.

Out on the world beneath him he looks from his high watch-tower;

No glance for the Senate Halls, where he ruled in his day of power.

Why should he care for the paltry plots of the petty brood,

Each one pursuing his own, instead of his country's, good?

With freer and fuller sweep he looks over sea and land,

With sight made clear by the touch of the dread Magician's wand;

His keen eye scans the Empire, wherever Britons dwell,

But first it rests on the people and the land he loved so well.

III.

Looking forth from his watch-tower, with eyes undimmed and free,

Down through New Zealand's future, he sees what we may not see-

Sees the full-ripened fruit, the wise laws that assuage

Arrows and darts of misfortune, sorrow and sadness of age;

Sees strong Plutus degraded, grinding Monopoly prone;

Sees men reap where they sowed, each one holding his own;

Infancy nurtured, Maidenhood guarded, and Motherhood blest;

Labour ennobled and richly rewarded with guerdon of rest;

Homes made brighter and purer, hearts more glad and elate;

Woman, co-equal with Man, sharing the duties of State;

Sees Humanity, Justice, and Love going hand in hand-

Progress and Peace and Plenty blessing this beauteous land!

IV.

Over a world-wide Empire he casts his sweeping glance;

Argosies, commerce-laden, on the ocean's broad expanse

Sees, as they speed on errands of love, goodwill, and peace,

Bearing joy to the nations and wasteful War's surcease;

Sees one free flag waving o'er all the Pacific Isles,

Canada grand in her strength, Australia wreathed in smiles,

Africa cleansed and purged of the alien helot strain-

Our race, pure, glad, triumphant, through all the proud domain.

These lands have heard him and heeded; his words were as pregnant seed,

And the golden grain is an Empire united in thought and deed.

Why, then, should women weep or the hearts of men be sad?

The fruit of his life's long travail he sees, and his soul is glad.

V.

Sleep, tired Worker, and, sleeping, see

Those glorious visions teeming-

See, in the days of the Yet to Be,

The world more glad and men more free,

Brotherhood reigning from sea to sea

And the Banners of Progress streaming!

Sweet be your rest on that windy hill,

While all that we wish for and work for still-

The final triumph of Good o'er Ill-

You see in your peaceful dreaming!*J. Liddell Kelly.

* From the New Zealand Times.

The first Dominion Day

In Nelson, on the first Dominion Day, 26 September 1907 the Colonist newspaper took a shot at Prime Minister Ward:

Our brave defenders stand to arms,

Our priests their banners bless,

Our lasses flaunt their latest charms,

Our babies effervesce …

We merely find another name;

An honoured one we lose;

All other things are yet the same,

What other would you choose?

Sir Joseph chuckles in his place,

For kudos he will gain:

His pipes have played a pretty pace;

We dance and feel quite vain.

At 11 a.m. on the steps of Parliament the governor, Lord Plunket, invited Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward to read the proclamation of dominion status. He did so, and shouted out, ‘Three cheers for the King’ (the response was ‘hearty and unanimous’, according to the Evening Post).

Ward also issued a message to the people of New Zealand. He spoke of preserving ‘the purity of your race’ and urged ‘equal opportunity to all’. ‘Trust the future of our Dominion not to increasing wealth, but rather to an ever higher manhood and womanhood, to a wider enlightenment and humanity disciplined by the needs of industry, by temperate living, and by those healthy and beneficent tasks that beget advancement and which should be the price of promotion in a free country.’

That evening, Parliament adjourned early so politicians could enjoy an oyster supper. Parliament Buildings put on a grand show. What is now the Parliamentary Library shone like a beacon. Bright lights across the front of the building spelt out ‘Advance New Zealand’ and the words ‘Colony 1840’ and ‘Dominion 1907’.